Researchers make scientific history with new cellular connection.

Researchers from the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute have revealed an exciting and unusual biochemical connection. Their discovery has implications for diseases linked to mitochondria, which are the primary sources of energy production within our cells.

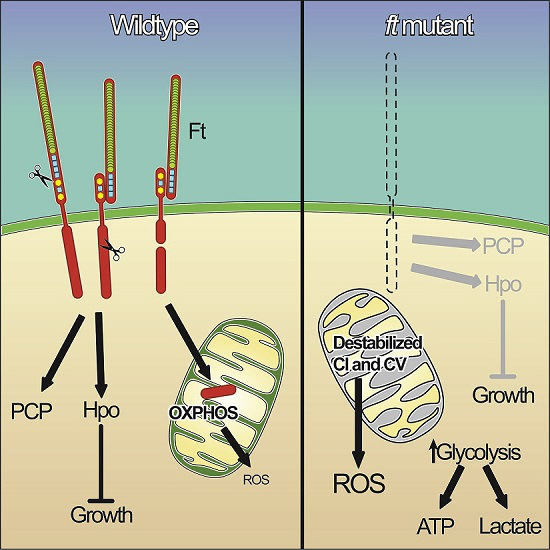

The team has an international reputation for their work in understanding how cells become organized into tissues and how growth is regulated during development. The group focuses on mutations in the fat (ft) gene. The protein product of this gene, called ‘Fat’, acts at the cell membrane to promote adhesion and communication between cells. Mutations in ft can cause cells to overgrow and become tumours. This occurs partially through the Hippo pathway, a pathway that is frequently activated in cancers such as liver, breast, ovarian and sarcomas.

Fat proteins are typically thought to work at the cell surface, but the team’s paper, published in the journal Cell, uncovers for the first time that a piece of the Fat protein is actually processed and delivered into the mitochondria where it influences the energy status of the cell. Importantly, when this particular component is missing, the energy generating pipeline inside mitochondria become destabilized, leading to loss of energy production.

The researchers were amazed to find that Fat proteins interact directly with mitochondria in a cell, regulating the cell’s metabolism. The team state that they still want to know how a cell knows when to release the Fat protein into mitochondria, but for now, this new linkage opens up a whole new way of thinking about how cellular energy is controlled as well as new ideas about how to shut down cancer cell growth.

When mitochondria stop working properly, cells no longer have an efficient energy source. Instead, cells will switch to glycolysis to produce the energy they require, known as the Warburg effect. Similarly, tumour cells have glycolytic rates up to 200 times higher compared to normal cells. Since the mitochondria is responsible for producing energy for essential cellular functions, problems with mitochondria can also lead to illnesses such as Type 2 diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, heart disease, stroke, and Alzheimer’s disease.

The team has been evaluating their unique discovery in fruit flies, since they serve as a powerful model for human mitochondria. Their next steps are to test these findings on human cells. This new finding that links the cell membrane to mitochondrial function is important since it defines a totally new mechanism of cellular regulation.

The team are now investigating the specific role the ft gene plays with the hope of identifying new treatment targets for cancer and other diseases related to Fat malfunction.

Source: The Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute

In normal cells, such as the image on the left, a piece of the Fat protein is processed and delivered into the mitochondria where it influences the energy status of the cell. In mutated cells, this particular component is missing, causing the energy generating pipeline inside mitochondria to become destabilized, and leading to loss of energy production. Credit: Dr. Helen McNeill, Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute.